SF 133 Guide: Federal Government Accounting Training on Budget Execution Reports

What Is the SF 133 and Why Does It Matter?

Picture this: October rolls around each year. Agency accountants and budget officers stare at spreadsheets. Treasury and OMB analysts wait for data to roll in. Somewhere, an auditor is mentally preparing questions.

At the center of all this activity is the SF 133, a deceptively simple form that holds together federal budget execution, accountability, and auditability. It's one of the most consistent and comprehensive tools the government has for translating financial activity into budget terms.

If you work in federal financial management, understanding the SF 133 isn't optional. It's fundamental to Yellow Book audits, OMB Circular A-123 testing, and preparing accurate Agency Financial Reports (AFRs).

The SF 133 Fulfills Critical Legal Requirements

The SF 133 serves several statutory purposes that make it essential for federal government accounting:

First, it ensures the president reviews federal expenditures at least four times per year as required by law.

Second, it reports on unliquidated obligations, unobligated balances, canceled balances, and adjustments made to appropriation accounts during completed fiscal years.

Third, it monitors the status of funds that were apportioned in the SF 132 (Apportionment and Reapportionment Schedule), as well as funds that were not apportioned.

Beyond legal compliance, this report provides consistent presentation of information across every agency. That consistency matters. It allows consolidation and comparison across the federal government. It creates a historical reference that's extremely useful when the President's Budget is being prepared. And it helps budget analysts in Congress (and even private citizens) identify patterns in obligations.

Finally, and this is critical for financial statement preparers, the SF 133 helps you tie your agency's financial statements directly to budget execution. Specifically, you'll use it to reconcile with the Statement of Budgetary Resources (SBR).

The Four Sections of the SF 133

Section 1: Budgetary Resources

You'll see lines for appropriations, spending authority from offsetting collections, unobligated balances brought forward, and other adjustments that affect total budgetary resources.

Section 2: Status of Budgetary Resources

You'll see new obligations, apportioned balances (both Category A and Category B), unapportioned balances, and the breakdown between unexpired and expired funds.

Section 3: Change in Obligated Balance

You'll see obligations incurred, outlays, recoveries of prior year obligations, and the net change in obligated balances.

Section 4: Budget Authority and Outlays, Net

You'll see budget authority broken down by discretionary and mandatory, outlays from new authority versus prior year balances, and distributed offsetting receipts.

How the SF 133 Connects to Other Budget Reports

The budgetary resources section (Section 1) is the only section that's common across all three reports. The SF 133 and the SBR also share the status of budgetary resources section (Section 2). The remaining sections of the SF 133 (change in obligated balance and budget authority and outlays net) are unique to the SF 133 and are not shared on the SBR or the SF 132.

This matters because when you're reconciling reports, you need to know which sections should tie together and which sections serve different purposes.

When Do You Submit an SF 133?

You Must Submit an SF 133 For:

You Do Not Submit an SF 133 For:

Understanding the Fund Lifecycle

The key to knowing when to submit is understanding where your fund is in its lifecycle:

Unexpired: When a fund is in its period of availability, it's unexpired. You can obligate this money for new commitments.

Expired: For five years after that period ends, the fund is expired. You cannot obligate expired funds for new commitments, but you can still disburse money to pay existing obligations.

Canceled (Closed): After that fifth expired year, you cancel the funds. That's a closed TAF. No new obligations, no new disbursements. These don't get reported on the SF 133.

How Federal Agencies Submit SF 133 Reports

GTAS is the backbone of federal financial management for budget execution reporting. If you're working in federal government accounting, you'll become very familiar with this system.

Monthly Submissions for Quarterly Requirements

Monthly reporting facilitates several essential benefits for government accounting training and operations:

First, it helps Treasury meet OMB's requirements by allowing them to compile financial reports in a timely and accurate manner. Monthly submissions alleviate the year-end burden.

Second, it allows Treasury to perform month-to-month analysis on agency data, which helps the Fiscal Service address open audit findings related to compilation of the Financial Report of the United States Government.

Third, it helps identify issues earlier in the fiscal year so Treasury can address them before year end, again alleviating that year-end crunch. This is critical for Yellow Book audits and financial statement preparation.

Finally, it supports OMB's budget submission requirements and the associated deadlines for working with Congress, and it allows agencies to be more accurate and efficient with loading their data.

What This Means for You Practically

The good news? Monthly reporting gives you multiple opportunities to catch and fix errors before year end when the stakes are highest. Your monthly rhythm also means you can track your obligations and outlay patterns throughout the year. This is especially important during continuing resolutions or when you're monitoring spending against apportionments. You'll see trends emerge that help you manage your budget execution more effectively.

The Reporting Calendar Explained

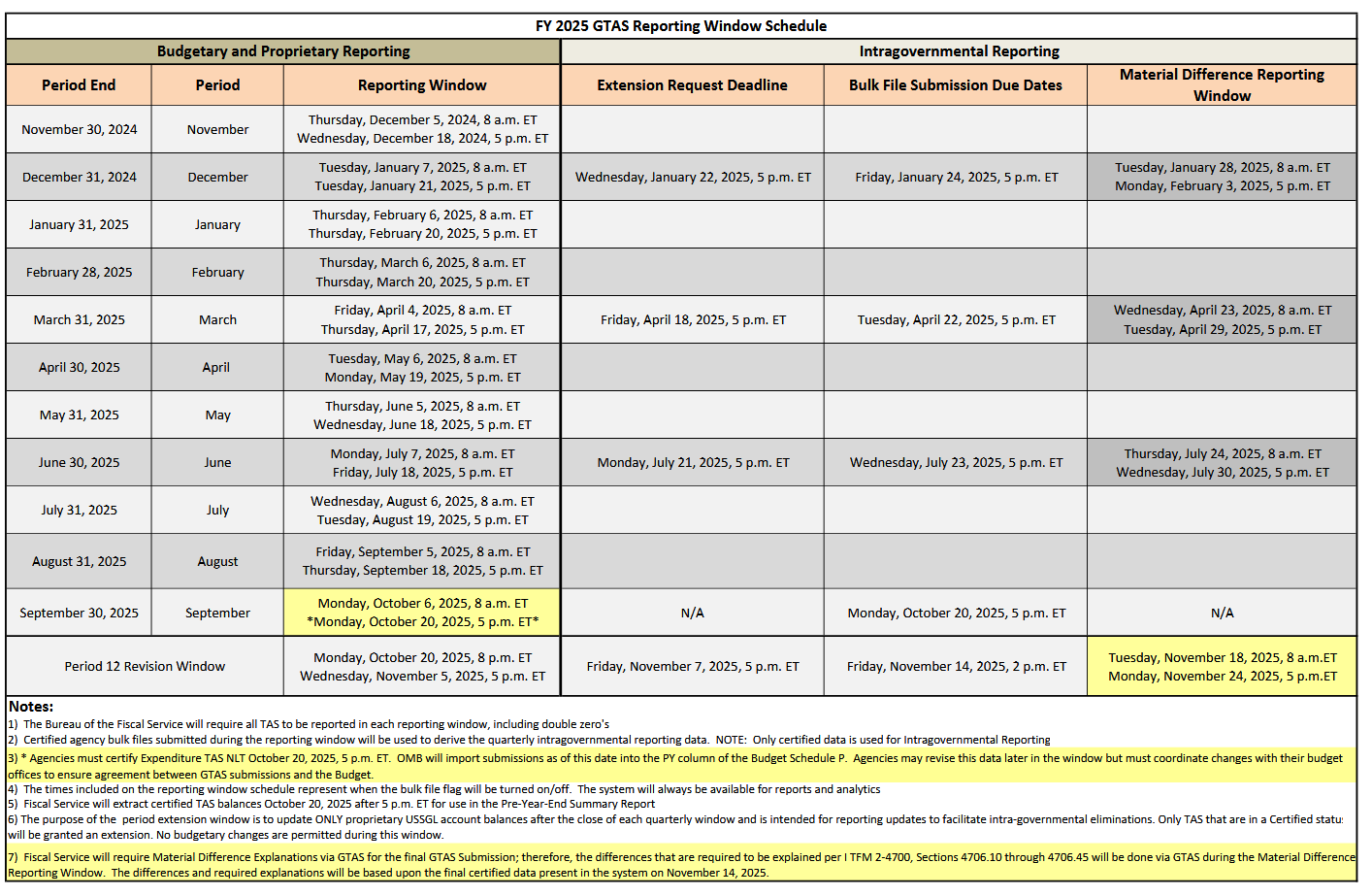

So in early December, you report October and November. In January, you report December, and so on, until early October when you report September. In October, there's also a Period 12 revision window.

Why not report for twelve months straight? If you had to report GTAS data for October while also closing your books and doing financial reporting for the prior fiscal year, that would be a mess. This eleven-month schedule gives you breathing room by having that first GTAS submission in December.

This schedule is published annually by Treasury, and you can find it in GTAS. The reporting windows show you exactly when submissions open, when they're due, and when Treasury closes the window for each period.

What Comes Next

In Part 2 of this series, we'll cover:

- How to use the USSGL crosswalk to build an SF 133

- Understanding the critical account attributes that drive accurate reporting

- Step-by-step examples using real USSGL accounts

- Practical tips for maintaining clean GTAS submissions

- Common mistakes and how to avoid them

The SF 133 isn't just a report you read. It's a report you create every month using your agency's USSGL trial balance. Understanding the mechanics of that creation process is essential for anyone working in federal financial management.

Ready to master federal budget execution reporting? Visit FederalFinanceCPE.com for accounting CPE online. Our online governmental accounting courses and government accounting training cover the SF 133, Treasury Account Symbol structure, federal financial management, and the practical skills you need for Yellow Book audits and federal government accounting work. Earn NASBA-approved governmental accounting CPE credits while building real-world expertise. Continue to Part 2: Creating the SF 133: Mastering the USSGL Crosswalk